The Many Not the Few – the stolen history of the Battle of Britain by Richard North. (This is the first of what I hope will become an occasional series of book reviews)

Richard North is a defence analyst and blogger. In this book he seeks to dismantle the myth that ‘The Few’ – the small group of fighter pilots who fought in the ‘Battle of Britain’ – saved Britain from invasion in 1940. North paints a much wider picture.

Hitler’s war aim was to force Britain out of the war rather than to defeat Britain, and to achieve this he had to force Britain to come to terms. To do this, he mounted a three-fold pressure. While diplomatic approaches seeking a settlement were made in secret, Hitler attempted a blockade, threatened an invasion, and sought to undermine the morale of the British population. The blockade consisted of attacking shipping bringing supplies to British shores, and attacking our ports from the air. Preparations were made for an invasion, a threat which also had the useful result of keeping within Britain forces that could have been used elsewhere for fighting in the Mediterranean or protecting convoys. Finally, air attacks were meant, among other things, to undermine the will of the British people to resist. If the people had not been determined to resist, Churchill would have been forced to come to terms, just as various countries on the Continent had done.

Resistance to Hitler’s aims at sea was just as important as the battle in the air, and so was the determination of the people to resist bombing attack. North points out the importance of wartime propoganda: claims of Luftwaffe losses were greatly exaggerated, compounded by the comparison of Fighter Command losses with total German fighter and bomber losses. In fact, if one counts the total losses in all air commands on both sides, British and German aircraft losses were almost equal. The existence of an invasion threat was useful to Churchill, who could point to it to stiffen the resistance of the British people.

In actuality, the invasion threat was just that, a threat. The Germans gathered large numbers of barges in visible preparation for an invasion, but unlike the Allies in 1944 they did not possess any of the specialist ships and landing craft required for an opposed beach landing, in which material had to be unloaded at speed. German generals and admirals knew this and kept pointing it out to Hitler. Even when it became clear that an invasion was not practical, the Germans kept up the pretence of preparation to maintain the pressure on Britain.

On the whole, the British Government did a good job of resisting the Germans, though there were significant lapses. Even though fighter pilots were a scarce resource, no official efforts were made to rescue them should they have to bale out over the Channel, and many were drowned. Air-sea rescue was only set up much later. The Germans on the other hand had an efficient seaplane rescue service. The British rather unsportingly used to shoot these planes down.

Initially, little or no provision was made to aid people bombed out of their homes, and they were left to go from one office to another trying to get relief, being treated rather like cross-channel migrants. In a notorious incident hushed up at the time, a school acting as a relief centre for the bombed out, who should have been bussed to safety, suffered a direct hit from a bomb which killed a large but still unknown number of people. The provision of deep shelters was actively refused as a matter of policy, and people were forbidden from using the Underground stations as deep shelters. Only when people started breaking in, or buying platform tickets to gain access, was this policy reluctantly reversed. In various places, people used dank and facility-less tunnels as ready-made shelters. With a bit more incompetence in this area, a change in public mood could have lost us the war.

The question of war aims was another bone of contention. Those of a socialist bent wanted the Government to promise a workers’ utopia, wheras Churchill was determined that after the war things would remain the same as before. This thinking found its outlet in the myth of ‘The Few’ versus a ‘people’s war’.

This is a thought-provoking book and well worth reading.

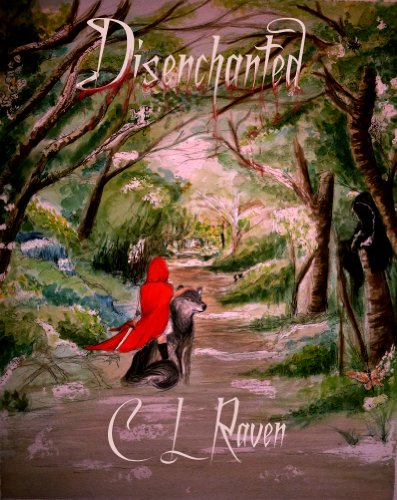

This is a short story collection from two Welsh sisters writing as CL Raven. This is a collection of traditional folk tales rewritten with a dark-fantasy feminist twist. The first story opens with ‘Once upon a time there was a beautiful princess called Snow White. Who the hell calls their child that?’ – an opening line that prompted me to buy the book. The opening story ‘Long Live the Queen’ is told from the point of the wicked stepmother as she tries to get rid of that irritating goody-goody, Snow White.

This is a short story collection from two Welsh sisters writing as CL Raven. This is a collection of traditional folk tales rewritten with a dark-fantasy feminist twist. The first story opens with ‘Once upon a time there was a beautiful princess called Snow White. Who the hell calls their child that?’ – an opening line that prompted me to buy the book. The opening story ‘Long Live the Queen’ is told from the point of the wicked stepmother as she tries to get rid of that irritating goody-goody, Snow White.