Paradise Lost – Smyrna 1922 by Giles Milton.

Smyrna was a city on the western coast of Anatolia, in what is now Turkey. If you are looking for Smyrna on a map, it is now known as Izmir. Before the First World War, Smyrna was a prosperous city with a varied population comprising Greeks, Turks, Armenians, Europeans and Americans mostly living in their own sectors of the city. The prominent buisnessmen and merchants were often those known as Levantines, families with English names who had never been to England, and the like, who lived lives of great opulence, living in grand mansions on the outskirts and ammusing themselves with yachts and summer houses. The various ethnic groups lived in relative harmony under the Ottoman regime. At this time, large numbers of Christian Greeks, and also Armenians, lived within the declining Ottoman empire.

Signs of strain emerged during the first world war, which the Ottomans entered on the side of Germany, and as the war progressed, the Ottoman empire engaged in unsuccessful campaigns and edged closer to disintegration. Discrimination against the non-Turkish populations started, spurred by central edicts, though a liberal Turkish governor of Smyrna strove to protect the city’s non-Turkish residents. By the end of the war, the victorious Allies had occupied parts of the dying Ottoman empire including Constantinople, Smyrna and other parts of the coast, while a nationalist Turkish regime headed by Mustafa Kemal (later Ataturk).was emerging in Anatolia.

The Turks, infuriated by Armenian uprisings during the war, deported hundreds of thousands of them in 1915 in the notorious Armenian genocide. (Why the Turks should expect any loyalty from a people they had already repeatedly persecuted is beyond comprehension.) Milton clearly has no truck with excuses for the genocide and claims that its murderous tactics were sanctioned at the highest level.

Worse was to come. The Greeks. encouraged by the Allies including Britain, embarked on an invasion of Anatolia with the aim of creating a greater Greece. At first this went well, but the Greeks over-reached themselves in the semi-desert interior, and by 1922 were being driven back with losses, while all the towns and villages fought over were sacked and burnt, and populations attacked, by one side or the other. By September 1922 the victorious Turks were entering Smyrna. At first the inhabitants had little fear of anything dire happening, as a fleet of warships from various nations had gathered in the harbour. However many Turks wanted revenge for atrocities committed by the Greeks, and the Turkish forces included many ill-disciplined irregulars.

As the disorganised, ragged and half-starved Greek troops flooded into the city, hoping to be taken off from the harbour, the situation deteriorated, with Turkish forces looting, raping and killing, with particular attention to the Armenian quarter. Then sections of the city were set ablaze. According to Milton this was entirely deliberate and carried out by the Turkish forces. Within days, hundreds of thousands of desperate refugees were crowded on the waterfront with flames on one side, the sea on the other, and subject to random murderous attacks by Turkish forces. The international ships in the harbour refused to embark any of them lest they offend the new Turkish regime.

Eventually the Greeks, shamed by an American citizen, sent ships to take off many of those trapped on the quayside, but by this time most of Smyrna (except the Turkish quarter) had been burnt to the ground, and eventually an estimated two hundred thousand people had died of various causes – murdered, burnt, drowned, or taken on death marches into the interior. One witness commented that it made him ashamed to be part of the human race.

Those who escaped were left peniless, robbed as they left, and spent many years living in poverty in Greece and elsewhere. The great Levantine families likewise never recovered, with all their wealth and property stolen or destroyed.

Before long, a further, greater exodus of desperate refugees began as Greece and Turkey exchanged their remaining minority populations to create the two monotheistic states that remain today.

This is a powerful account that will be of interest to students of history, and those seeking an explanation for animosities that linger to this day.

As s footnote, Louis de Bernieres novel “Birds Without Wings” is set in the same tragic period and refers to many of the same events.

In this one, the struggle between rebels and the Empire comes to a conclusion, ancient energies are awakened, and Imperial Princess Maihara keeps alive her ambition to become Empress. (to order, search for Kim J Cowie on Amazon.)

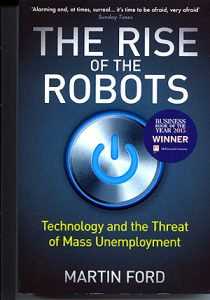

In this one, the struggle between rebels and the Empire comes to a conclusion, ancient energies are awakened, and Imperial Princess Maihara keeps alive her ambition to become Empress. (to order, search for Kim J Cowie on Amazon.) Technology and the threat of mass unemployment.

Technology and the threat of mass unemployment.