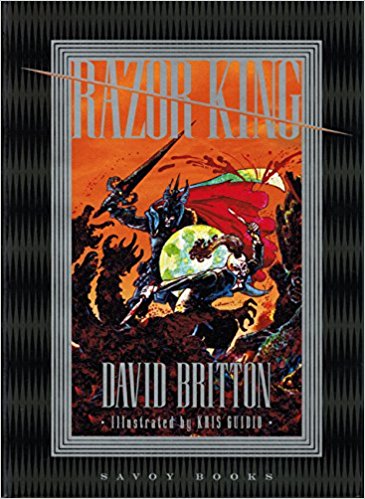

Razor

King by

David Britton, Savoy Books, Oct 2017, 300pp, £20.

Razor King is

David Britton’s seventh novel, the latest in his series of

absurdist novels about the Jewish Holocaust.

The

novel has a loose narrative of sorts, but mainly consists of a series

of fantastical series of scenes and descriptions of three or four

main characters, the razor-wielding Lord Horror, engaged in

dispatching Jews with his razor, and his two grotesque associates

Meng, a sexually voracious half-man half-woman, and his emaciated and

more reflective brother Ecker. There is also Meng’s pubescent

daughter, the winsome La Squab. There are also two talking cars with

libidos and an alien boy made of confectionery. The settings involve

among other things crematoria, the Wild West and a ship crewed by

rats. Britton certainly has a vivid imagination and a knack for

putting his creations on the page.

Needless to say, Britton does

not in any way endorse anti-semitism, but is attempting to expose its

psychopathic and un-empathetic nature.

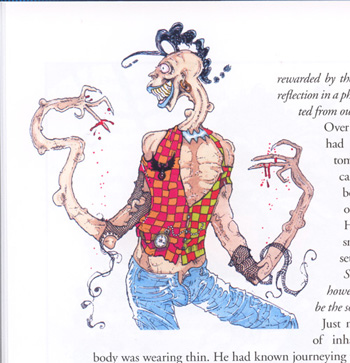

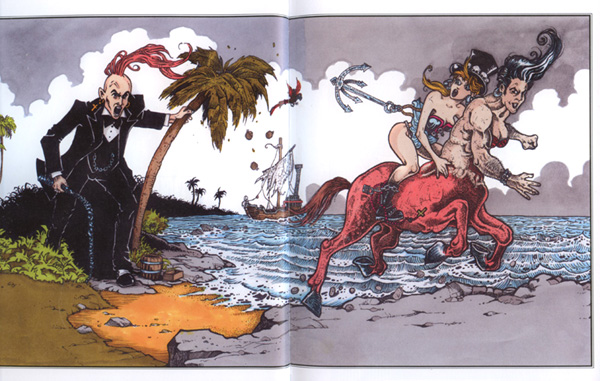

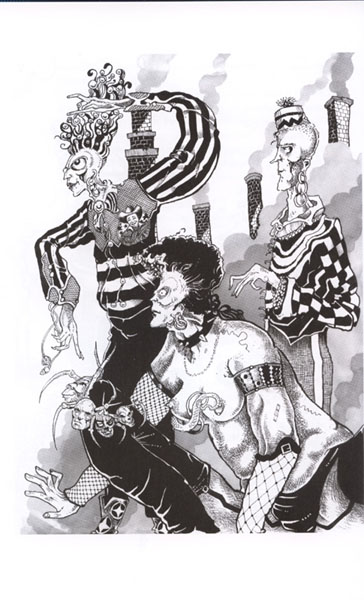

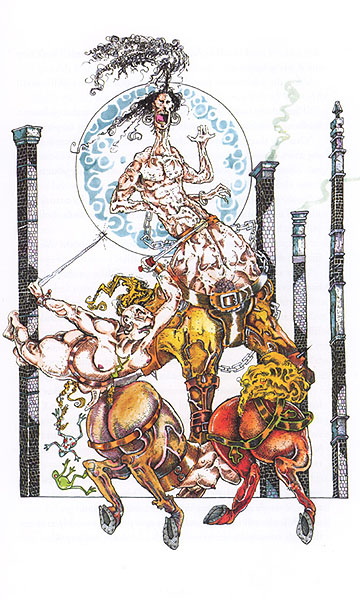

Continuing a trend begun

with La Squab in 2012, Razor King is illustrated throughout by Kris

Guidio, this time entirely in full colour. The book contains thirty

double-spread full colour illustrations, depicting Britton’s

grotesque characters, along with crematoria, Ken Reid’s elf

characters Fudge and Speck (from Reid’s comic book republished by

Savoy) and various characters redolent of Edgar Rice Burrough’s

books. The images contain some cartoon nudity.

Let’s be clear, this book is for adults only, and further to that, it’s for adults not easily offended. This is a brutal satire on anti-semitism, and everything in it references Hitler and the Jewish holocaust. While reading it however, I was forcibly reminded of a more recent event, the ethnic cleansing of the Rohinga from Burma.

‘Razor King’ is a significant exercise in transgressive speculative fiction, extending on an established tradition, and deserves some serious attention. The artwork alone would make it worth examination. (CD).